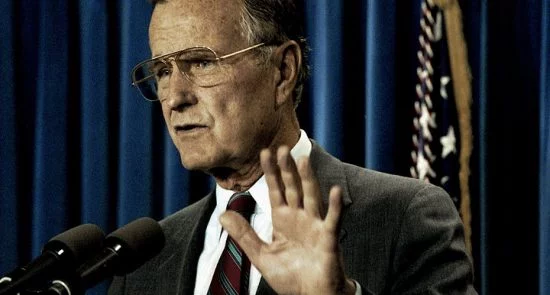

George H.W. Bush Was The Last President To Really Get Tough With Israel

One of George H.W. Bush’s greatest accomplishments, a flurry of even-handed diplomacy that set the stage for the first direct Israeli-Palestinian peace talks, has received relatively little attention in the analysis of his legacy that followed his death on Saturday.

Ariana News Agency- As part of his efforts, Bush threatened aid to Israel to nudge it in the direction of peace — making him the last American president to take such strong measures against the American ally. And, for a time at least, he got his way.

“Bush’s foreign policy legacy, especially on the issue of Israeli-Palestinian peace, cannot be overstated,” said Daniel Kurtzer, a longtime U.S. diplomat who helped shape Bush’s Middle East policy. “His willingness to be tough on all parties … ushered in a period of intense diplomacy involving Israel and all of the Arab world.”

Had the United States government continued Bush’s tough-love approach, rather than abandoning it, Kurtzer and other foreign policy veterans argue, the U.S. may have succeeded in brokering the kind of lasting peace deal that still eludes Israel and the Palestinians.

“It’s pretty remarkable that no Republican or Democratic president since has been willing to put meaningful pressure on Israel,” said Khaled Elgindy, a fellow at the Brookings Institution who advised Palestinian negotiators from 2004 to 2009. “Even as they have learned what the peace process has required, they’ve been less willing to do what’s needed.”

‘One Lonely Little Guy’

In the wake of the first Gulf War, which ended in February 1991, then-President Bush was at the peak of his power on the global stage. He had successfully expelled the Iraqi military from Kuwait, a U.S. ally and major oil producer ― all while managing to insulate Israel, almost entirely, from retaliation at the hands of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein.

Bush decided that Arab-Israeli peace was next on his list of international accomplishments. To that end, his famously assertive Secretary of State Jim Baker laid the groundwork of what would become a multilateral peace conference in Madrid, Spain, in October 1991. Israel and a host of Arab governments sat down, under American supervision, to discuss their thorniest differences, chief among them, the status of the Palestinian people.

In a nod to Israel, the Palestinian Liberation Organization, a militant political organization that represented the Palestinian national cause, was not present. Instead, Palestinian representatives participated as part of the Jordanian delegation.

But a few weeks before the conference, the right-wing Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir asked the United States to guarantee $10 billion in loans Israel needed to help absorb hundreds of thousands of immigrants from the Soviet Union. Under the arrangement, the U.S. would have served as Israel’s guarantor with creditors, assuring it a much lower interest rate than it would have otherwise received in the credit markets.

The United States had already guaranteed a $400 million loan to Israel to absorb a smaller wave of Soviet Jewish immigrants in October 1990.

At the time, Baker had negotiated strong assurances from Israel that it would not use the funds to relocate the Jewish immigrants to settlements in the territories Israel occupied since 1967, which the U.S. viewed ― and, at least officially, continued to view for decades ― as a major impediment to peace.

When the U.S. sought to impose the same terms to the new tranche of loans, however, Shamir objected.

Bush stood his ground, insisting on delaying the entire loan guarantee for 120 days. He claimed he did not want a protracted debate with Congress over settlements to interfere with the peace talks; he likely also wanted to pressure a wayward Shamir into cooperating with the conference and burnish American credibility as a fair mediator with Arab nations.

Shamir thought that with the help of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or AIPAC, he could force Bush’s hand by mobilizing Congress to approve the aid immediately in defiance of the president.

Unmoved, Bush vowed to veto legislation that authorized the aid before the 120-day delay had expired. He took his case to the media, speaking at length about his stance in a press conference on Sep. 12, 1991. He famously portrayed himself as an underdog against the might of AIPAC and other pro-Israel groups, which had recently organized a massive lobbying day on Capitol Hill.

“I heard today there was something like 1,000 lobbyists on the Hill working on the other side of the question. We’ve got one lonely little guy down here doing it,” he said, eliciting laughs from the White House press corps.

Shortly thereafter, Bush prevailed in his game of chicken with Shamir and AIPAC.

Congress backed down. And when the U.S. finally guaranteed the loans in the spring of 1992, it did so using a new formula designed to offset Israel’s spending on settlements. It guaranteed $200 million less for each billion Israel asked for to account for Israel’s projected settlement spending.