Asia, Human rights December 24, 2019

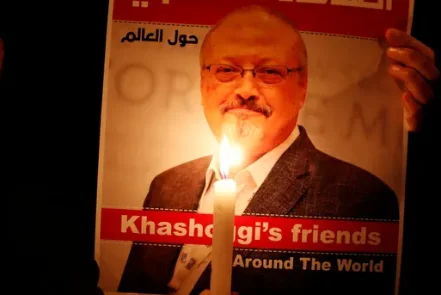

Short Link:Saudi Arabia Mocked Justice through Jamal Khashoggi’s Murder Case Sentences

on Monday, the authoritarian kingdom of Saudi Arabia sentenced five operatives to death for the grisly murder and dismemberment of the Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi, at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, in October, 2018.

Ariana News Agency-

Another three men were dispatched to jail; three more were acquitted. The outcome was, in the words of human-rights experts with whom I spoke after the verdict was announced, “typical Saudi justice.” The trial was held in secret. The government’s evidence was never publicly released. The convicted were never named, even in the verdict.

And the few diplomats allowed to attend the trial had to swear that they would not disclose any details or identities. Most strikingly, the three men widely believed to be ultimately responsible for Khashoggi’s murder—including the powerful crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, his close adviser, Saud al-Qahtani, and the former deputy head of intelligence, Ahmed al-Assiri—got off scot-free.

“This is not a surprise. It is true to form,” Sarah Leah Whitson, the executive director of the Middle East and North Africa division of Human Rights Watch, told me. “The Saudis are compounding their stream of laughable lies with a laughable verdict.”

Both the C.I.A. and the U.N. implicated M.B.S., as the crown prince is commonly known, in Khashoggi’s murder. During the past two years, the ambitious young royal has consolidated Saudi Arabia’s five major branches of power under his gold-embroidered robe. He has also been the key Saudi liaison to the Trump Administration and a close ally of Trump’s son-in-law and senior adviser, Jared Kushner.

Khashoggi, a former unofficial spokesman for the oil-rich monarchy, fled the kingdom in 2017 and took residence in the United States, where he became the prince’s most vocal and visible critic. Weeks before his death, Khashoggi told me that M.B.S., still only the heir apparent to the Saudi throne, had already become more autocratic than any of the previous six kings. He compared the prince’s absolute powers to those of Iran’s Supreme Leader: “He has no tolerance or willingness to accommodate critics.”

In one of Khashoggi’s early columns for the Post, he says that he has to write as his conscience dictates. “To do otherwise would betray those who languish in prison,” he writes. “I can speak when so many cannot. I want you to know that Saudi Arabia has not always been as it is now. We Saudis deserve better.”

M.B.S.’s culpability—and premeditation—was the issue implicitly on trial. The kingdom originally lied, saying that Khashoggi had walked out of the consulate shortly after he’d arrived. It took three weeks for the government to admit that he’d been murdered; it claimed that the execution was a rogue operation, despite the extraordinary planning required for a sophisticated covert operation on foreign soil.

Turkey then released videotapes of two Saudi hit squads—comprising fifteen people in total—arriving in Istanbul the day before the murder. It had video of Khashoggi going into the consulate.

Turkish intelligence recorded all that followed, including Khashoggi’s struggle to fight off Saudi security, his gasping suffocation, and the bone-sawing that followed, as his body was cut up into pieces. The Turks also had video footage of a body double—one of the men who had flown in for the operation—leaving the diplomatic mission dressed in Khashoggi’s clothing.